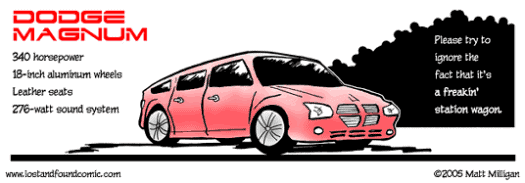

From Lost and Found, by Matt Milligan. Nevermind what it is… look at the shiny.

You can almost set your watch to it: every year some president or spokesman from a company that isn’t Microsoft makes the grandiose pronouncement that Personal Computers are dead, and that the successor to the PC just happens to be, by nothing more than fortuitous coincidence, something they happen to be selling at the time.

This time around it’s Johnathan Schwartz, president of Sun Microsystems. Sun actually has a grand tradition of heralding the end of Personal Computers — Sun has used the phrase “The Network Is the Computer” for years, trying to shift the focus of computer use to the internet, to programs that run over networks instead of on your hard drive… but I suspect they’d be happy with anything that would rip users away from Microsoft’s lock on desktop computers and get them to focus on other ways to “do stuff with those computer things.”

Of course, all these companies who talk about how the PC is going to be replaced by other things — usually the internet or a business network — try very hard to convince us that, from our perspective, nothing will actually “change.” Our end-user experience will be exactly the same, they claim. We won’t realize that when we boot up our machines we’ll be reaching across the internet to retrieve all our data, access all our programs, and do all the things we’ve been doing with our computers. Write a note to a friend, write the great American novel, balance your checkbook, do your taxes… even, God forbid, publish a web comic, all of these things can be done with programs on the internet, through your web browser, via java applets or Microsoft .NET, or something else they haven’t bothered to fill us in on, and — here’s the important part — we’ll never know the difference.

After carefully considering this Prophetic Vision of Silicon Developments Yet To Come, I have composed a response that I feel accurately sums up my opinion:

The problem with pronouncements like these (and even more, with the way that the computer press takes them at least semi-seriously) is that it reflects a level of laziness within the industry that is not shared by the people who make that industry far more rich than it really deserves to be. It assumes that the “Computer User” really is only one person, with one preferred method of Doing Things. And now that search engines on the internet are popular, the thinking goes, it’s obvious that this single, monolithic Computer User wants to use the Internet for everything, right?

Right?

Anyone?

Yeah, that’s what I thought.

While I’ll freely grant that there are a lot of people who probably use a web browser and an email program and not much more — the target market of people who want to turn the “network into the computer” — I think the companies who are trying to kill the PC in favor the network device, or the search engine, or whatever the flavor of the month is this week, are overlooking a rather important piece of the mystique that comes part and parcel with every PC that gets sold: PC’s like cars, represent a certain level of freedom and self-sufficiency that internet-centric platforms simply don’t have.

It’s not the “Computer,” stupid — it’s the “Personal.”

I could be wrong, but it seems to me that the reason people started buying computers in the first place was because computers were enablers — they made it possible to do things that were either too expensive or too difficult (or a combination of both) to do without them. The spreadsheet allowed you to ditch the ledger and the adding machine, and keep track of your finances even if you weren’t particularly good at math. The word processor allowed you to write and revise on the fly without wasting reams of paper due to spelling and typographical errors.

These programs weren’t (and still aren’t) particularly easy to use — every tool requires a certain level of familiarity in order to use it effectively — but they were accessible. Sure, the DOS version of WordPerfect cost hundreds of dollars back in the 80s, but a computer running WordPerfect and a dot matrix printer still cost significantly less than a printing press. A spreadsheet like Lotus 1-2-3 was, after you learned to use it, less expensive than hiring an accountant any time you wanted to figure things out.

That’s what the personal computer did — it allowed people to have access to tools that they previously couldn’t afford. And it was, for all intents and purposes, theirs to use as they saw fit.

Today, despite the fact that personal computers seem to be reaching the limits of their original design, they’ve succeeded when it comes to making work more accessible. My desktop computer, despite the fact that it is not what you would call a “high end workstation,” can very ably create graphics, animation, edit video, record music, and publish music in ways that exceed the capabilities of standalone products that existed twenty years ago. My laptop, which I use mostly for writing, email, browsing, and drawing and publishing my comic, weighs less than a portable typewriter from the 1970s and is far more useful.

And the thing that all those functions have in common — something that the people who are heralding the new age of internet computing are overlooking — is that I don’t actually have to be connected to a network in order to do any of it.

That’s right: if Verizon’s DSL connection crashes for some reason, I can still write, record, draw, design, even play games. Sure, I can’t check my email until it comes back up, and I can’t update my website until it comes back up — but I can write that email, and I can modify my website. That is the “Personal” part of the PC at work, and it’s something that goes away if the new focus becomes a network-distributed platform, where suddenly everything becomes dependent on whether or not your provider can keep everything running while managing to stay in business.

On the other hand, perhaps that’s the point. It seems we’re reaching a point with PC hardware and software where customers are going to say “oh, well, I guess I’ve got everything I need, then” — and stop buying it. When we decide everything we want to do is already loaded on our PC, and we have all the features we need, when we reach the point where version 15.0’s features make us yawn, and we lack any desire whatsoever to fork out the money for the upgrade, what’s a computer company to do? They can go the Intuit and the Microsoft route, which is to try and force their customers into buying into a “subscription model” for the software they run on their computer… or they can try to call the whole thing “passe” and try to convince people that they really want to do everything from a browser.

(Look at the date on that press release to get an idea for how long they’ve been trying to do this.)

Companies who aren’t Microsoft or Intuit seem a lot more interested in the latter approach, because it puts them on relatively equal footing as far as that market goes. It also allows them to proclaim themselves as trailblazers in a new computer revolution, which is always nice — being able to claim street cred when you’re trying to put one up over on the reigning 800-pound gorilla never hurts. But at the end of the day, this revolution isn’t particularly revolutionary: all they’re doing is re-inventing the wheel, only the end result isn’t quite as round.